Glitter + Ashes Read online

Neon Hemlock Press

www.neonhemlock.com

@neonhemlock

Collection Copyright © 2020

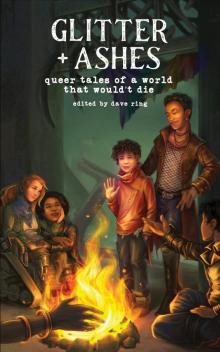

Glitter + Ashes:

Queer Tales of a World that Wouldn’t Die

edited by dave ring

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency.

These stories are works of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, organizations or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

“Apocalypse” by Saida Agostini originally appeared in the Barrelhouse Special Issue I’ve Got Love on My Mind: Black Womxn on Love, Feb 14 2020, edited by Tyrese Coleman.

Cover Illustration by Grace Fong

Cover Design by dave ring

ISBN-13: 978-1-952086-10-6

Ebook ISBN-13: 978-1-952086-11-3

GLITTER + ASHES:

QUEER TALES OF a WORLD

THAT WOULDN’T DIE

Neon Hemlock Press

What can we look for when we read stories of collapse and apocalypse while the world is on fire? It’s hard to know at first glance—perhaps, a map? Or a blueprint. Something to guide us forward, take us out of this mess. Reflections on the end of the world and its aftermath have been a crucible leading to so many incredible narratives that give those possible blueprints: Tank Girl and Mad Max: Fury Road, yes, but also The Fifth Season by N.K. Jemisin, Blackfish City by Sam J. Miller, and Parable of the Sower by Octavia Butler.

These stories show us that the end is not simply a dark road leading to more grit and doom. In that tradition, Glitter + Ashes: Queer Tales of a World That Wouldn’t Die is an anthology centering queer joy and community in the face of disaster, via the amplified horrors of our current trajectory as well as more haunted and sinister ills. We set out from the beginning to find scraps of hope in every ruined future, knowing that queer folks, especially those with less access to sociocultural capital, often must learn to find meaning within the fractures of all manner of broken terrain. Yes, you’ll read stories of folks learning how to get by, how to survive. You’ll also read stories of folks learning to love themselves, learning how to find one another in the darkness, and learning how to stand up for each other. Making something stronger and more beautiful.

I am grateful to be able to share the roleplaying game Dream Askew by Avery Alder with you at the end of the anthology. Dream Askew forgoes dice and uses shared authority to explore the collapse through a queer enclave. It’s a compelling, thoughtful system and I hope it gives you an opportunity to live and breathe the sort of stories that can become blueprints of your own.

If this summer has taught me anything, it is that there is beauty and power in refusing to back down, especially in the face of seemingly unassailable opposition. Even when the world is on fire. I’m humbled and inspired by the stories in Glitter + Ashes. Each of them is a bright torch against the cold night. Bear witness to their resilience and determination. Hear their laughter, and raise your fists with them.

May they give you the same solace they did me. May that solace be a commitment to nurture scraps of hope, glittering and fragile, amidst the ashes of today, not some uncertain future. Refuse to back down. And if joy is missing, may we come together to make it ourselves.

dave ring

June 2020

Washington, DC

On unceded Nacotchtank & Piscataway land

Wrath of a Queer God

Anthony Moll

Didn't My Lord Deliver Daniel

Christopher Caldwell

The Descent of Their Last End

Izzy Wasserstein

Soft

Otter Lieffe

The Black Hearts of La Playa

Jordan Kurella

The Bone Gifts

Michael Milne

When the Last of the Birds and the Bees Have Gone On

C.L. Clark

A Future in Color

R.J. Theodore

Champions of Water War

Elly Bangs

A Sound Like Staying Together

Adam R. Shannon

Be Strong, Kick Many Asses

Aun-Juli Riddle

Venom and Bite

Darcie Little Badger

The Currant Dumas

L.D. Lewis

The Limitations of Her Code

Marianne Kirby

You Fool, You Wanderer

Brendan Williams-Childs

A Party-Planner's Guide to the Apocalypse

Lauren Ring

Imago

A.Z. Louise

Safe Haven

A.P. Thayer

Note Left on a Coffee Table

Mari Ness

The Valley of Mothers

Josie Columbus

For the Taking, For the Making

V. Medina

When She Nothing Shines Upon

Blake Jessop

The Last Dawn of Targadrides

Trip Galey

The Dreadnought and the Stars

Phoebe Barton

Apocalypse

Saida Agostini

Dream Askew

Avery Alder

Acknowledgements

About the Authors

The first ones to go would be the tasteless, anyone who has wielded unrhymed sacred text as armament, made body holey with Leviticus or even denied a name at holiday dinner. I’d be an Old Testament type—no, Greek—know fear as I cast down my wisdom in the form of lightning bolts, flooding Southern towns that build billboards for blond Jesus. Thou shall have no other before me in hairy legs and platform heels. Next I’d come for the trailer parks (not that the salt of the earth have wronged, but to deny shame of my own genesis) leaving only the baby butch toughs to testify, to reinscribe the words awesome and enormity with the weight they’re due. The rich, I’d eat whole, consuming capital and shitting out bread and boutique health clinics. This hunger not only devastates, but lets rise thrift store monarchs, the most clever among you, now kings in their knock-off luxury, now queens in their shoplifted MAC. I’d tear to timber every suburban church, in part for their precepts but more for their aesthetic—how dare build anything but peacocked glory, stone and glass phalluses. Look now to the lesbian witches in hiking boots—let them show you what structures the moon desires.

I am everything you say I am. Witness my agenda: shade and spite, swallowing men whole.

Elijah came as himself, not as Eden. I was in my garden, pinching back the leaves of a garlic plant about to go to seed. A shadow stretched over me. I squinted up into the noonday sun. We were all leaner, but he looked gaunt. “What do you want, Eli?”

If you didn’t have a history with him, you could mistake Elijah’s unlined face, his louche posture, and his boyish pout for youth. But he had turned fifty in the decade plus since that last terrible argument, and to me, it showed. He was ashy. Bags under his eyes. The veins on the back of his hands stood out. “I didn’t come to fight.”

I dug into the earth with a spade. The smell of damp soil soothed me. “I assume that Eden does all the fighting nowadays?”

Eli shuddered. “She goes by Grandmother now. It’s a sort of euphemism. Like how all the names for bear are really ‘brown one’ instead—”

“I know about bears.” He always liked a lecture. “What do you want, Eli?”

H

e bit his lip. “It’s just that there’s a cantrip should prevent anyone from saying that name.”

“Eden?” I said, then finding his surprise infuriating, “Eden!” I shouted. “Seems like your raggedy spells don’t work.”

“On you, Deshaun. My spells don’t work on you! It’s why I’ve come.”

I stood up. Planted my heels in the earth. “You’ve come all this way to use me as a magical guinea pig? Where’s your gown? Where’s your knock-off Jimmy Choos? Your costume jewelry? How you gonna hex me without your evil queen regalia, boo?”

He spread out his hands.“You got it all wrong. I can’t blame you for that.” He looked down at his feet. “I came without any of that, without armor, without charms, to ask you to help me. I take care of survivors now. Most of ‘em barely more than kids. Grandmother is Eden’s role. She—I—look after them. But it’s not safe here. You know that. I need to get them to the city.”

This was why he’d come. Another foolish grand adventure. “I’m not young. Leave me with my grief and my plants.”

He sneezed, the way he always did when he was about to cry. “I can’t protect them all. I need you.”

I looked up at him. Deflated. Needy. Found it hard to hold onto my anger. “What you need is some lotion for your ashy ass.”

And so it went.

Elijah had taken up residence in the ruin of a grand old mansion. Out front, a heroic fountain choked with duckweed and water hyacinth. Mardi Gras beads slung over the enormous chandelier in the foyer. Threadbare rugs on the terrazo. The grand staircase was lit by hundreds of candles, ranging in size from tealight to altar pillar, in all the colors of the rainbow. He descended from above, the flickering light playing against his cheekbones. He wore a silken turban and a Schiaparelli pink dressing gown, not quite Eden’s deadly glamour, but definitely not just Elijah.

I was sitting in a folding lawn chair. He reclined in a moth-eaten chaise longue. He picked up a wine glass from an old steamer trunk littered with them and held it to the light. It was none too clean, but he poured it full of red, and drained it in a single pull. He smiled. “The children have only ever seen me as Grandmother. And I think it’s important for their faith. But you knew me before.”

“We only lived together for six years,” I said.

“Six years of you critiquing my makeup and making sure I got enough sleep so no one would know I robbed your cradle.” He poured another measure of wine. “You did get my marrain’s gumbo recipe out of the bargain.”

“‘If the roux don’t look like Wesley Snipes, it ain’t ready.’ So, what does Grandmother wear? I assume it isn’t a housecoat and a showercap.”

Elijah stood. He placed his wine glass back on the steamer trunk and made a complicated gesture with his left hand. The dressing gown shimmered, the bodice constricted around his bosom, and sequins covered it decolletage to waist. The skirts bloomed out and sprouted marabou feathers along the hem. His turban grew feathers and beads. His voice became mocking and seductive. “These are the rags I wear around the house. But for our grand voyage? I have something truly spectacular.”

Eden extended a hand to me. She had an immaculate French manicure. “Come doll, time to meet the kids.”

Hand in hand we strolled out back into a courtyard with an empty pool lit by paper lanterns. About a dozen figures arrayed themselves around a bonfire burning in what was the pool’s deep-end. A young man clambered up the pool’s ladder. Early twenties. Thick, wavy black hair. He wore a rumpled gabardine pea coat. He was striking, and I felt awkward noticing it. Eden dropped my hand. “This is Juanjo, the oldest of my children. Sometimes the most responsible.”

Juanjo bowed deeply at the waist, then grabbed my hand and kissed my ring finger, as if he were greeting the pope. He caught my eye. “At 23, I’m not much of a child.”

Eden slapped him on the bottom. “The impertinence! You’ll be grown when Grandmother says you are.”

Next were two girls in their late teens. Sabrina, redbone, tall, gawky, and angular. Shirelle, dark, short, and plump. You wouldn’t mistake them for sisters, but they had that strange facial similarity long time lovers get; something in the way they held their mouths.

Then a tiny person dressed in purple with a scarf wound around their mouth. They introduced themselves as Clay.

Each was younger than the next until I got to a high yellow boy with a kinky mop of hair. He couldn’t have been older than thirteen. Eden poked him in the belly. He giggled.

“EJ here is twelve.” Eden said.

“Twelve-and-a-half!”

“Twelve-and-a-half. He’s too young to remember the Breaking.”

An unexpected surge of envy roiled in me.

Grandmother’s gown looked too heavy for any single person to wear, yet Eden promenaded in it, on better days she sashayed. It was covered in ornamentation. Mirror fragments on the bodice, hemmed in by pearls, sequins, tiny crystals. The skirt was oceanic, both in volume and and accoutrement; nets held together panniers encrusted with shells, coral, over aqua taffeta. The train extended five feet behind.

Picking our way east over roads with surfaces cracked and buckled from the encroaching woodlands meant that our procession was more funereal than stately. When the sun started to dip towards the horizon, we made camp. Everyone had a job. Clay, David and Lee pitched tents. Juanjo and Nacho cooked the vegetation I’d foraged through the day. Shirelle and Sabrina spun a web of protection above the camp. It was both a physical thing, spun out of gossamer threads Shirelle conjured, and a mystical barrier called into being by Sabrina’s song. Even EJ helped fetch water and kindling for the fires.

Once we made camp, I helped Grandmother undress, and like some fairy tale where some miraculous beast sheds its skin and becomes an ordinary man, watched her shrink into Elijah. None of the children, not even trusted Juanjo, were allowed into Grandmother’s tent. Elijah’s rationale was that seeing him as a middle-aged man instead of a beautiful titan would shake their faith when they need it most. He was drained and fragile at the end of the day, and being his confidant forced a sort of intimacy I was no longer used to. I brought him his food, fed him when he was too tired to lift spoon to mouth.

About five days into our trek, I brought Elijah some nettle soup and fried mushrooms. He sat with his back to me, and the criss-cross of scars across his ribs and spines looked like a tributary map. He received those marks during the time we weren’t speaking, and I didn’t have it in me to ask. “Brought your supper.”

His eyes were tired. “What I wouldn’t give for a two piece and a biscuit. No matter how greasy.”

“Today we have puffball mushrooms fried in expired cooking oil, if you’re looking for an unhealthy snack.”

Elijah sucked his teeth. “Speaking of snacks, I see my eldest has his eyes on you.”

“Juanjo?” I thought of how his hand lingered on mine when I showed him how to pull up hairy bittercress without bruising the leaves. “He’s been helping me forage. Good head for mycology. He found the giant puffballs, and warned off Clay from the Jack-o-Lanterns when they—”

“Those ain’t the kind of mushroom head he’s after, DeShaun.”

My mouth felt dry. “You nasty! He’s barely more than a child.”

“He’s a man. And it ain’t like there’s a surplus of fine ass in the world.”

My cheeks were hot. “Don’t want no more of this talk.”

Elijah leaned back into a pile of cushions. He closed his eyes. “Don’t say I never warned you.”

I tried to keep my distance from Juanjo after that conversation with Eli, but I only had the flimsiest of excuses. He did have a good head for mycology, and it was hard to forage on my own for enough food to feed the camp, particularly as we got further into the wilds and more of the flora was the twisted and useless sort made by the Breaking. We fell into a sort of companionable silence. I could feel his interest, and to be honest, I returned it, but we never let that thing get in the way of the work.

W

e had been lucky on our trek so far. We heard a pack of wolves in the hills, but they’d stayed away. We lost the better part of a day when Lee got sick after being stung by a Broken wasp. Uneventful, for the most part.

Juanjo and I were picking sloes and rowan berries at the edge of a meadow and keeping an eye on EJ while he gathered dried grass and twisted it into bundles. Juanjo was singing a song in Spanish about a botecito, and had just got to the part about ‘una isla dulce amor,’ when an unmistakable sound killed the song in his throat.

Broken crows aren’t black like their untransformed cousins, they’re a vibrant purple. Twice as big, they don’t caw. Instead, they have a horrible screech like a cross between an air raid siren and a wounded child. As silent in flight as owls, you don’t hear them unless they’ve found something to eat. They have a taste for meat. The sky turned purple as they flowed like smoke over the rowan trees and across the meadow.

“EJ!” Juanjo yelled. He ran towards the boy who dropped his bundle of grass and was standing stock still staring at the murder heading for him. Juanjo tackled the boy and covered his small body with his own as the first birds began to divebomb. I knew a song of the earth and started chanting as the swirling purple mass descended.

A shout pealed. Clay ran towards us, scarf unwound from their mouth. They breathed out a gout of flame that scattered the murder and sent the smell of singed feathers sharp in my nose. The birds wheeled on their aggressor just as Clay inhaled deeply for another blast.

But it wasn’t flames that came next. From behind Clay, a brilliant white light made mockery of the November noonday sun. I shielded my eyes, but even closed, I could make out the after-image of Eden’s form. Her cold light scattered the crows, who screamed up and away in panic.

When the light faded, I ran to Juanjo and EJ, both motionless on the ground. I placed a hand on each of them and felt. EJ had a concussion and would have some bruising, but would otherwise be alright. Juanjo was hurt badly. Bleeding from several places. A punctured lung. Broken bones. I could mend a broken bone with time and concentration, but this was beyond me.

Glitter + Ashes

Glitter + Ashes